The Walk is a film directed by Robert Zemeckis – it is a film that unfolds strong emotions on the side of the reception by the spectators. A strong and physical emotion that hits who’s watching and keep him at the edge of the seat until it reaches its conclusion: which are the patterns that help this overwhelming sensations to reach the audience, especially when we already know what the ending will be?

Please note that this analysis may contain SPOILERS If you have never watched this film, please come back after you did – it’s really a film not to be spoiled.

A moving walk

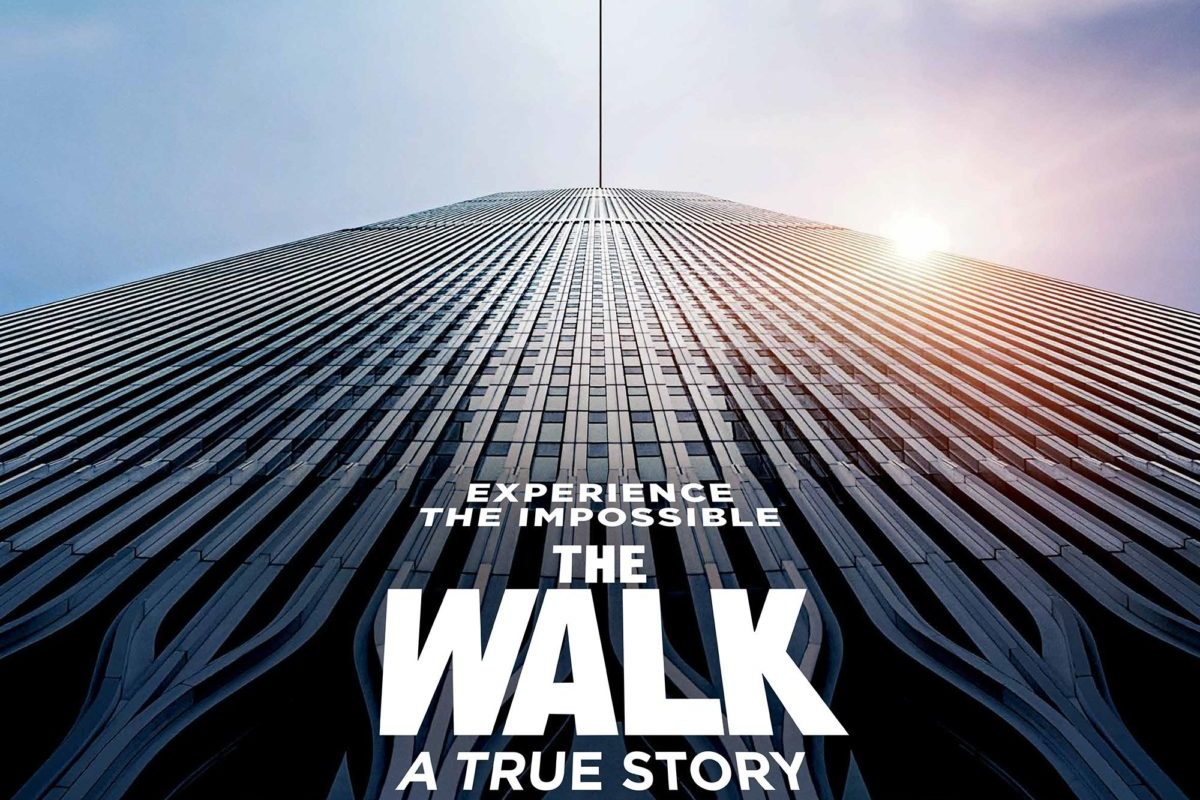

Robert

Zemeckis’ The Walk is centered on the walk between the Twin

Towers carried out by the well known wirewalker Philippe Petit.

The

story is quite known: on the morning of the 6th of August

1974, Petit walked over a wire between the two towers with the help

of just a pole for the balancing.

The operation and the event are

notoriously successful and the film does nothing to hide it. Zemeckis

(and the screenwriters) engineer their narratives so that this stays

clear: at the beginning of the film – and in a recurrent scene –

Philippe Petit (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) says it will show us how “it

happened” setting the film in the past.

In some way, the Towers

are a symbol of the fall and death that accompany arm in arm the

human work and the images of the morning of the 11th of

September 2001 are probably working in our brain in a subtle way

during the entire sequence of the walk.

What we are interested in though is not really a review of the film and its narratives, but more an investigation on the ways that the director unfolds the emotions and play with them in the key moment. The paradox is: we know how it ends and we still shake with tension. How does this happen and through what processes?

What’s behind an emotive response at the cinema?

Behind the connection that happens between the spectator and the film there’s a process called empathy which is also a pre-condition for any emotional connection.

Fundamentally, two distinct neurophysiological systems are in place in this contact: the system that carries out the most immediate, immersive and physical contact – responsible for a connection that relies on the embodied simulation – and another that is situated on a reflective state (cognitive one) and it’s responsible for a less immersive contact and it relies on the Theory of Mind.

These two systems, balancing each other, help the proximity of the spectator’s Self to the Other which is the aesthetic.

In order to leverage one or the other side of this fundamental balance, two different aspects are called in by the narratives and the staging techniques – para-dramatic factors and eso-dramatic(1):

– para-dramatic factors: it’s about indications, directions that reassure our hypothesis on intentions, motivations, memories and beliefs of the others: importance is given to events not observed online but memorised (past/future – “it happened”). Amongst the cinematographic tools used to reach this goal there’s often the minimalism of the action. This factor helps creating a settled emotional reaction.

– eso-dramatic factors: it’s about perceptual markers that emphasizes body states: importance is given to events observed live. Amongst the tools: sounds, body attitude, gestures, human-centred hearing and seeing and camera movements simulating the human sight.

These two factors are at the core of the empathetic contact with a film.

How “it happened”

A very interesting question that can be made when we talk about cinema is how is it possible that some emotions and emotive states continue being there even when we know exactly how the scene, the even or the film itself is over? This obviously signal less importance in the narrative device, whilst the emotive suture is stronger more than the reflective one.

An answer goes under the name of firewall hypothesis, developed by David Bordwell (2): according to him the amplification of our emotive involvement (even active when we watch a film a second time, or a third, etc.) has to be placed on a series of very low-level structures that the best filmmakers use in a way that it exerts the attractive and pre-cognitive power of the cinema – through formal practices like close ups, quick movement of camera, editing, sound designs and immersive techniques.

What can be added to this hypothesis, given the evidences of some of the new neuroscience studies is that, the experience of a film like The Walk is really to be included in the embodied simulation territory as this theory is able to underline an immersive and sub-personal emotional reaction thanks to actual physical and body stimulus.

Adriano D’Aloia, in his review, talks about a form of an “hyper-solicitation of the vestibular system (that governs the sense of balance)”(3).

This solicitation of the balance is integrated to the firewall hypothesis, as the director stages a number of shots that try to tickle the physical level of the vestibular system (through eso-dramatic factors). If the 3D of the projection adds that depth that helps in this direction the perception of the height (finally a good use for the 3D that can be seen as functional), even the 2D version is not shy of this depth.

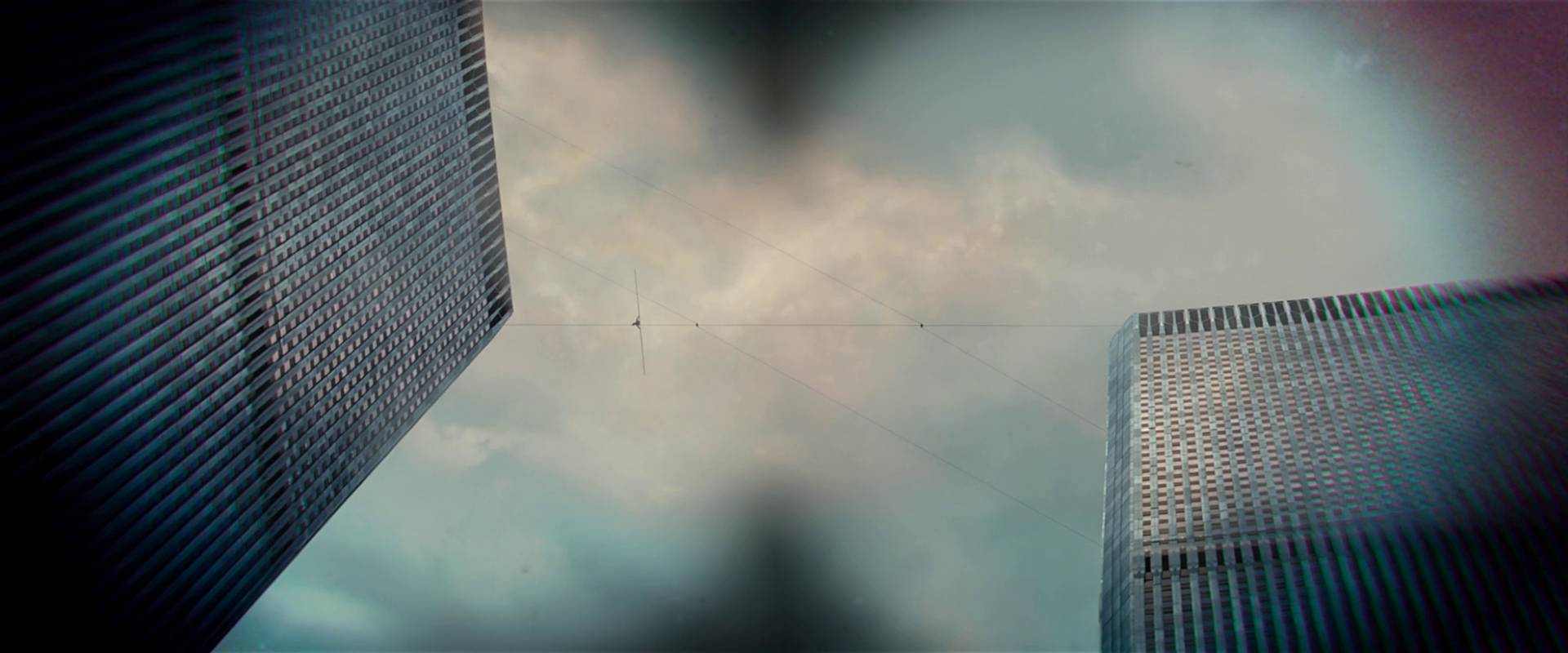

The beginning puts us right up on the wire and the camera movements follow the character: this kind of tickling of the vestibular system is particularly strong in the plongéeand consequent contreplongée shots from the point of view of the audience on the street.

The physical and mental processes of the spectator (with the concern of what the protagonist might be thinking as we don’t have a lot of access to his thoughts) are in this moment of the film equivalent and in balance – the tension is pretty much all given by the physical sensation of vertigo.

The editing shows us a tie where there could be a potential problem, nonetheless the walk seems completed as Philip reaches the other tower and then, right when the tension seems to loose up, he decides to go back and do the walk in the opposite direction: there’s now a distance between the calmness of our protagonist and our frightened feeling facing the gratuitous sensation of this unnecessary walk back (that we interpret as danger) and the para-dramatic factors are now in short-circuit.

This distance is perfectly staged in the stunts and tricks that Philippe is doing on the wire: this trembles every time and the protagonist has to resettle his balance every time. At this point, as if an accidental fall would not be enough to keep us on the edge of the seat, a particular narrative device is played: before the events taking place on the Twin Towers, Philippe hurts his foot. The sequence showing this injury adds immediately on the cognitive level of the spectator a doubt on the actual end result of the fact.

As spectators of hundreds of films we’ve built a sort of cinematographic memory and we perfectly know the set-up and payoffs mechanisms of the film narratives: we know for instance that when something is shown (a gun), it’ll be used at a later stage (it’ll shoot) – or at least in most of the films.

The unnecessariness and the contrast with the danger are signalled in a shot that, relying on the physical level (foot) communicates a pain equally as physical as the shot itself. And through what we know thanks to the embodied simulation (according to which our mirror neuron system activates the parts of the brain active when we are, in first person, in the action/scene/fact/event just without activating the motor system) everyone is able to live the feeling (virtual and/or refined) of the pain in this dangerous situation and the tension keeps building up: the protagonist is still 400m high and the film’s editing never miss a chance to remind this.

Not happy yet, Philippe lies does on the wire and the camera flies down from above him to the spectators looking from below. This moment signals a third act (inside the same scene) in which the threat seems to grow and Philippe hastens to reach the end (the seagulls, bad weather conditions).

When Philippe is standing up though, the wire trembles so much he’s having issues to resettle his balance. At the same time one of the security measures breaks and give a shock to the protagonist’s balance. Everything shakes, his foot is unstable on the wire and this give the spectators a pure thrilling moment (both the cinematographic spectators and the diegetic ones that are now adherent – definitely not a case that they’ve got a visual device like the binoculars as to symbolize others visual devices).

Zemeckis is basically signalling the spectator position that he intended to draw for this scene and our brain is invited to simulate not only the person doing the action, but even the ones who are looking.

But once more our hero manages to get

back his sense of balance. Zemeckis then decides to point his finger

to the physical alarm: the blood coming out from his foot is on the

wire. But again, nothing is happening with the injury – the

interesting thing about this is that the set-up

didn’t lead to a payoff

in a classical way (although some films break this rule,

as well – thankfully) but it’s used only towards the empathy

connection in place and the simulation thanks to the mirror neuron

system so that it just heightens the tension.

The

weather is changed, there’s a storm approaching and the wind

completes the load of the staging as well as the helicopter that

seems to be flying too close to the wire and makes Philippe’s balance

(and ours) shake. We’ve now reached the last three steps. We know –

through the narratives – that Philippe is not infallible as he

already showed a lack of focus once more on these final three steps.

It’s happening again, the wire trembles, the policemen waiting for

him watch terrified but are not able to do anything (just like us).

We’ve really reached the edge of the seat – the emotional reaction

is complete. Philippe makes it, overcomes the last of the

difficulties and it’s all over.

We, on the other hand, have lived a complex and complete emotional experience that has put us on a wire (400m from the ground) and at the same time on the witness stand. A difficult position for the clash of eso and para-dramatic factors and the idea that something that has already happened can’t go wrong constantly tested by the staging of the director and his mise-en-scene.

A tension that has definitely frustrated our possibilities of action (and the motor system) but that kept us sutured to the screen for a very long and very trying experience. But, we will back again on those wires, or maybe, we’ll just be back on the same seat we were, ready for another film and another thrilling experience.

And you, what do you make of this film?

You don’t know what film to watch tonight? Please have a look at our Film Alphabet page.

NOTES:

(1) Gal Raz, Talma Hendler, ‘Forking Cinematic Paths to the Self: Neurocinematically Informed Model of Empathy in Motion Pictures’, in «Projections», n° 8, issue 2, Winter 2014

(2) David Bordwell, Kirsten Thompson., Minding Movies: Observations on the Art, Craft and Business of Filmaking, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2011

(3) Adriano D’Aloia, ‘Schermi a strapiombo’ in «Segnocinema» n°197, Gennaio-Febbraio 2016